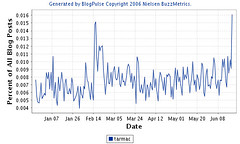

The buzz around passenger’s being held on planes on the tarmac against their will is skyrocketing. Above is a BlogPulse chart showing the percentage of all blog posts that mentioned the keyword “tarmac” over the past six months. That February 14 spike was driven by the JetBlue fiasco, and the very recent spike seems to be driven by a number of new incidents, facilitated by the lobbying efforts of the Coalition for an Airline Passengers’ Bill of Rights. (Btw, I was scheduled to fly JetBlue that Valentine’s Day.)

I happened to be a passenger on United Airlines flight 17 last Tuesday, stuck on the tarmac far longer than I would’ve liked. Five minutes after leaving the gate at JFK airport, bound for San Francisco, we were told we’d have at least a one hour delay. Well, that one hour turned into nearly four hours. My afternoon flight from East Coast to West Coast turned into a red-eye flight (a paradox), with me arriving in San Francisco early the next morning. With my luck, I had a middle seat on a nearly full flight.

The real tarmac action, though, was not aboard my flight. It was aboard many other flights, as evidenced by my aircraft’s channel 9, which was playing live the discussions between all the pilots and JFK’s air-traffic controllers. There were nonstop jokes, debates, frustrated rants and even pleas among the pilots of the roughly 75 other planes jockeying to take off that late afternoon and evening. Several pilots were reporting highly anxious passengers demanding to exit their planes, and demanding “straight answers” whether there’d actually be a takeoff (many flights were receiving false signals to depart). It was a schizophrenic mess.

Can somebody answer this simple question: Why can’t the airlines prohibit boarding unless they know — for sure — that their planes will take off? Where’s the breakdown in communication?

As far as I know, none of my fellow passengers actually requested to exit the plane, so I can’t say we were held against our will. I thought the pilot and crew handled the situation relatively well, keeping a sense of humor, offering frequent updates and serving beverages and food. The pilot said the plane had enough fuel to fly faster (albeit less efficiently) to make up time. When we finally arrived in San Francisco, the crew gave us food vouchers and coupons for discounted flights in the future. None of the restaurants in San Francisco airport were open, so they had sandwiches, snack items and beverages waiting at the gate upon arrival.

Perhaps United Airlines could’ve done a little more to build customer loyalty out of this difficult experience — like fully refunding passengers for their tickets, as JetBlue has done for me in the past in such situations — but to its credit, UA also could’ve done a whole lot less, as some other airlines did that day.